More than just a bad smell: Odour pollution and health in Aotearoa New Zealand

by Jonathan Jarman, Lou Wickham

Summary

Historically, foul odours were believed to cause illness and efforts to reduce their impact influenced urban design and public health laws. Research over the last 50 years has re-established odour pollution as causing adverse health effects as well as affecting community mental health.

Such incidents are common in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ); a search of news media identified 36 examples of communities in NZ experiencing significant odour problems between 2016 and 2025. In a case study from 2014, 13 people had symptoms severe enough to seek medical attention due to foul odours from a wastewater treatment plant.

Even though regional councils are the lead agency for managing odour under the Resource Management Act 1991, public health services have a role in advocating on behalf of communities affected by odour pollution.

“The stench invades everything, it gets right inside my house. I can taste it when I'm talking - it's revolting. I suffer from sore throats, sore eyes, headaches, shortness of breath and I miss all my friends. No one wants to come to Bromley anymore.”

This is how a resident described the experience of living close to the Bromley Wastewater Treatment Plant in 2022.¹ While most people accept that persistent foul odours can be very unpleasant, odour complaints are often viewed by regulators as an annoyance rather than a health hazard than can make people sick.

Odours and health

Until the golden age of microbiology between 1820 and 1890, it was generally believed that foul odours caused ill-health.² The word miasma comes from a Greek word meaning pollution.³ Many of the towns and cities in NZ designed in the 19th century show evidence of the response to the miasma theory with parks, green spaces, and the drainage of wetlands.⁴ The current public health legislation in NZ, the 1956 Health Act, still has sections such as statutory nuisances and offensive trades which are linked to 19th-century views of public health.⁵

With the arrival of the science of microbiology, foul odours as a cause of illness slipped out of favour unless levels of specific airborne chemicals reached levels demonstrated to cause toxic poisoning effects. Poisoning arising from chemical contamination of the environment is notifiable to the Medical Officer of Health under section 74 and Schedule 2 of the Health Act 1956. In contrast, becoming physically ill with vomiting and headaches because of a foul odour is not notifiable, despite symptoms being similar to poisoning--see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Reporting pathways under the Health Act 1956 (based on the mechanisms of odour-induced health effects outlined in Odours and Human Health)⁶

Odour pollution is common in Aotearoa New Zealand

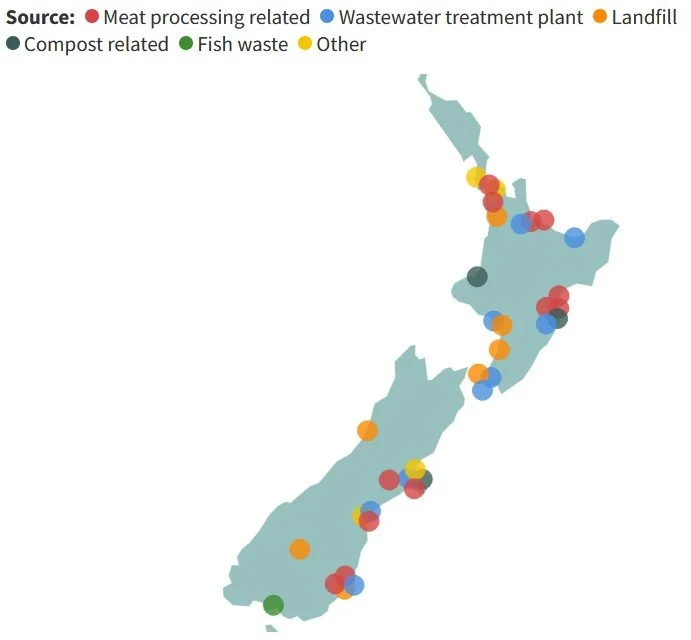

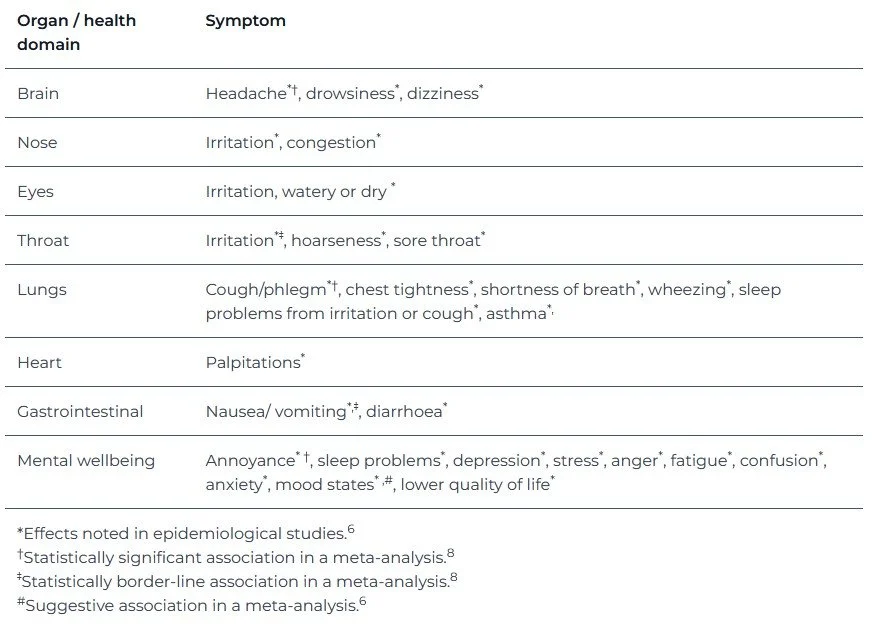

Odour pollution incidents are common and are a leading cause of environmental complaints to local authorities.⁷ A search of news media stories identified 36 persistent odour pollution incidents between 2016 and 2025. The most common sources of the foul odours were meat processing related (33%), wastewater treatment plants (25%), and landfills (20%). Some of the odour pollution incidents had lasted years or even decades. In total, 18 out of the 36 news articles described significant quality of life impacts such as social isolation, having to keep doors and windows shut even on warm days, and being unable to spend time outside when the foul odours were strong. We summarise the types and locations of incidents in Figures 2 and 3, with full details in Appendix 1.

Figure 2. Sources of persistent odour pollution reported in New Zealand news media, 2016-2025

Note: Based on a total of 36 incidents

Figure 3. Locations of persistent odour pollution incidents 2016-2025

Link here to interactive map

A bad smell is a signal to the nervous system to stay away

A large number of studies show that health and wellbeing are indeed linked to environmental odours. A review of more than 50 studies published between 1975 and 2013 found that residents of communities located near odour-emitting facilities were found to report a higher number of health symptoms compared to residents of control communities.⁶ A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 odour studies found a statistically significant association between populations exposed to odour pollution and adverse health effects such as headaches, coughing, and phlegm.⁸

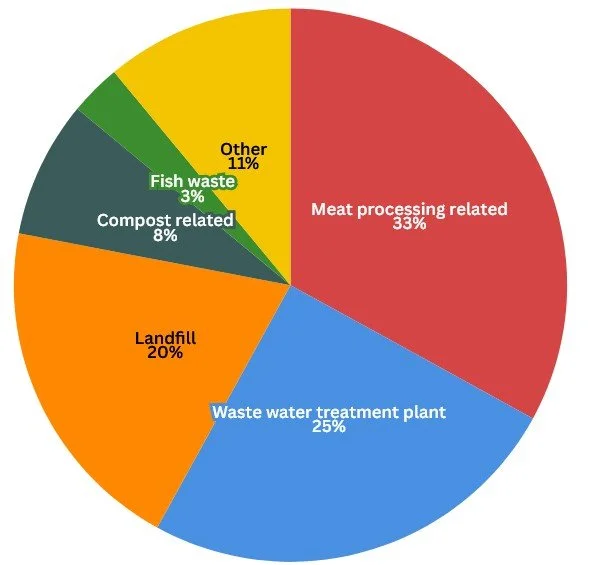

Smell is the oldest sense of the five senses from an evolutionary perspective.⁹ For humans, smell is a gatekeeper sense—a bad smell is a signal to the nervous system to stay away.⁹ Exposure to foul odours is associated with stress and annoyance, and the level of annoyance is strongly associated with symptoms that impact quality of life and mental health as shown in Table 1.⁶ ⁸ ¹⁰ Different life experiences and natural variation within communities can result in different sensations and emotional responses by individuals to the same odorous compounds.⁷ ¹⁰

Table 1. Common symptoms from exposure to environmental odours ⁶ ⁸ ¹⁰

Case study example - decomposing dairy waste at Eltham, Taranaki

Between 3 October 2013 and 28 October 2013, Fonterra discharged three million litres of buttermilk and 150,000 litres of raw milk into a covered anaerobic digesting pond located at the Eltham Wastewater Treatment Plant. The pond had been closed previously because it did not work. Odour complaints started almost immediately, and the people of Eltham suffered offensive odours for many months. General practitioners reported 13 people to the Medical Officer of Health with suspected odour-related illness, though none met the threshold of “poisoning”. ¹¹

The devolution of air quality management to regional councils under the Resource Management Act 1991, has largely overshadowed the statutory nuisance sections of the Health Act 1956 that relate to offensive odours.⁵ The South Taranaki District Council was eventually fined $115,000 and Fonterra fined $192,000 for breaching the Resource Management Act 1991. ¹²

Conclusion

Persistent foul odours from industrial sources, wastewater treatment plants, and landfills are common in Aotearoa New Zealand. Odours that are managed as annoyances by regional councils can cause symptoms similar to chemical toxicity including headaches, nausea, difficulty concentrating, loss of appetite, stress, insomnia, and physical discomfort, and can have a significant impact on community mental health. It is clear that the current environmental approaches under the Resource Management Act 1991 are not fully protecting communities from prolonged exposure to odour pollution. There is a strong case for public health services to do more to advocate on behalf of affected communities to improve, protect and promote their health and well-being.

What is new in this Briefing

There is extensive international evidence linking odour pollution to ill-health.

Repeated exposure to offensive “non-toxic” odours can cause symptoms similar to chemical toxicity.

Foul odours that impact communities are common in Aotearoa New Zealand and at times have lasted for years.

Regulators often view offensive odours as an annoyance for a small number of individuals rather than a hazard that can adversely affect health at a population level.

Implications for public health policy and practice

Primary prevention would include industries doing more to control odours, being a “good neighbour”, and improved zoning to further separate residential areas from the sources of offensive odours.

The 2016 NZ Good Practice Guide for Assessing and Managing Odour ⁷ needs to be updated to reflect the literature and explicitly address the potential health impacts of odour on communities.

General practitioners in localities with odour pollution should be reminded to notify all illnesses suspected to be caused by chemical contamination of the environment to their local Medical Officer of Health.

The National Public Health Service should proactively advocate on behalf of communities adversely affected by offensive odours, even once the risk of poisoning and chemical toxicity is excluded.

Author details

Dr Jonathan Jarman, retired Medical Officer of Health of 28 years and currently a student with the Department of Science Communication, University of Otago.

Lou Wickham, Director, Emission Impossible. As an independent, private consultant, Lou Wickham has previously provided advice to local government, public health agencies and private industry.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jayne Metcalfe and Prof Nick Wilson for their peer reviews of the final draft, and Dr John Kerr for suggestions and assistance with data visualisation.

Appendix 1: News media reports of persistent odour pollution incidents 2016-2025

Download pdf